Introduction

This paper focuses on the concepts of transference and countertransference occurring in the therapeutic situation, synchronicity that can be interpreted along with these, and the phenomenon called “intersubjective field or matrix” that is generated by and within the analytic dyad, all of which will be examined from a Jungian perspective. In order to explore these notions, I shall start with Carl Gustav Jung’s psychology, more precisely with his position on the analytic situation, transference and countertransference. Then I discuss some relevant theories of important Jungian and post-Jungian authors, followed by a description of synchronicity, its modern scientific explanation and potential clinical applicability.

The analytic relationship according to Jung

Discussions of the occurrence of countertransference in the analytic situation and the question of its applicability date back to the early period of psychoanalysis (Samuels, 1989, 105.). While Freud (1910 [1957]; 1913 [2001]) believed that countertransference originates from the analyst’s complexes and internal resistances that are activated by the relationship with the patient, and he scarcely revised his views about this subject over time (Samuels, 1989, 105.), Jung’s ideas of countertransference were more positive than those of the father of psychoanalysis (op. cit. 107.). In his Problems of Modern Psychotherapy (1931 [1985]), Jung describes the analytic situation as a mutual influence between doctor and patient which is essential in the healing process. He writes:

“In any effective psychological treatment the doctor is bound to influence the patient; but this influence can only take place if the patient has a reciprocal influence on the doctor. You can exert no influence if you are not susceptible to influence. It is futile for the doctor to shield himself from the influence of the patient and to surround himself with a smoke-screen of fatherly and professional authority. By so doing he only denies himself the use of a highly important organ of information. The patient influences him unconsciously none the less, and brings about changes in the doctor’s unconscious which are well known to many psychotherapists: psychic disturbances or even injuries peculiar to the profession, a striking illustration of the patient’s almost ‘chemical’ action. One of the best known symptoms of this kind is the counter-transference evoked by the transference.” (op. cit. 109.)

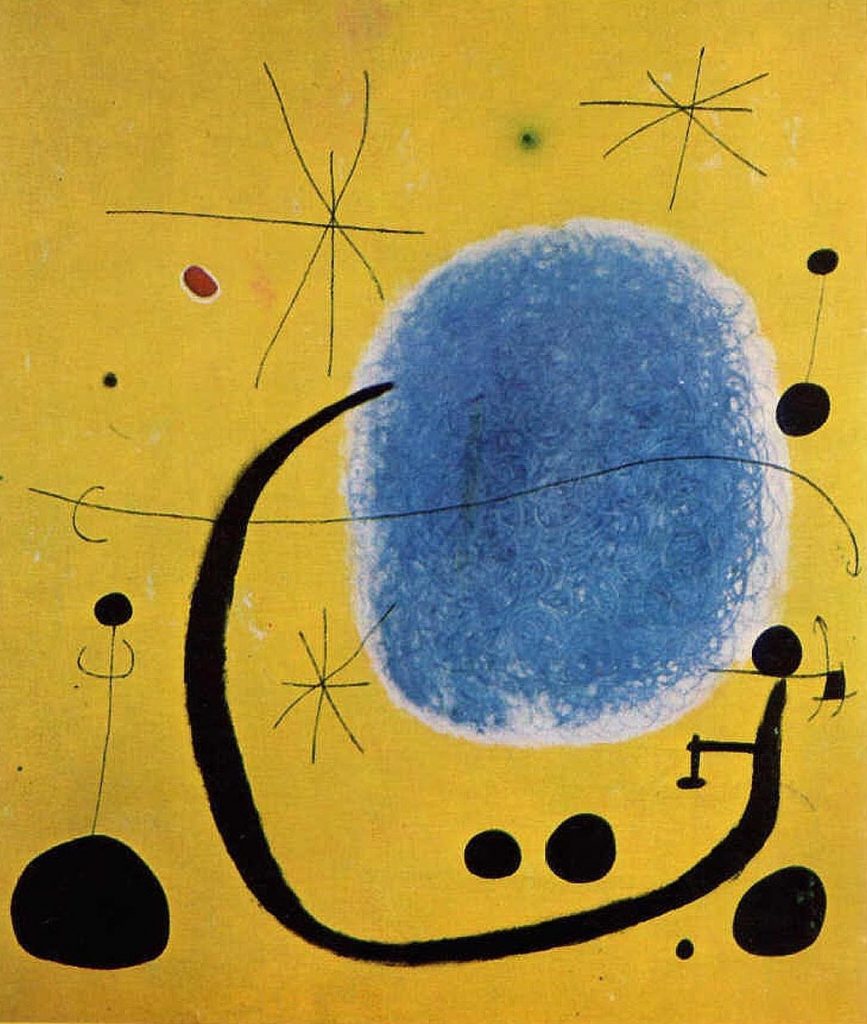

As we can see in Jung’s view, a “highly important organ of information” is in operation in order to evoke changes in the other person’s unconscious processes, emphasising the usefulness of influence and the reciprocal nature of the analytic relationship. In another work dedicated to the subject, entitled Psychology of the Transference, Jung (1946 [1985]) tried to capture analytic transactions operating on both conscious and unconscious levels with the aid of alchemical imagery and operations, which can be examined from two points of view (Carter, 2010, 201.): on the one hand, the tension between the conscious and the unconscious within the individual, and on the other hand, the tension between analyst and patient, which can symbolically give rise to a “third” one, which, by exceeding and transcending the previous opposite polarities, creates a new, previously unimaginable meaning, which is substantially more than the sum of the parts. Such a synthesis of opposites in analytical psychology is named a transcendent function. In her study of the Jungian interpretations of intersubjectivity and countertransference, Linda Carter (2010) emphasizes that in his theory of individuation – which is one of the cornerstones of his work about the psyche – Jung focused on the transformative aspects of change, the future unfolding of the psyche contrary to Freud’s reductive approach, focusing on the past and early events.

In Jung’s theory, the symbols of the unconscious foreshadow a progressive development towards a person’s new attitude on the one hand, and induce tension between conscious and unconscious levels on the other, which can be elaborated by the method of amplification (see Jacobi, 1999; Hill, 2010). Amplification is joint work between analyst and patient during which they try to find analogies to the archetypical pattern inherent in the symbol, using the realm of myths, folk tales and cultural examples. By doing so, they expand and deepen its meaning, which thus originates from the analytic relationship while also being embedded in a larger cultural context (Carter, 2010, 201.).

In Carter’s view, Jung’s ideas delineate contemporary issues such as the questions of interaction and intersubjectivity, emergence, and complex adaptive systems (CAS). Carter emphasises that intersubjectivity refers not only to the processes of transference and countertransference in the analytic relationship but also to a reality created by both participants in which new, interactive opportunities can emerge along with old patterns. Thus, the analytic dyad itself is an emergent phenomenon that depends on the interactions taking place in and defined by a certain, unique moment and is located in an archetypal field. Referring to Jung’s (1946 [1985]) alchemical metaphor, the participants of the analytic dyad are in conjunction with each other. Therefore, understanding how participants are present in the relationship, how they reflect on it and apply the possibilities of metaphors and analogies is essential for potential change and individuation.

The field generated by the participants of the analytic dyad defined by Carter (2010, 202.) as an “intersubjective matrix” coincides with psychoanalyst Thomas Ogden’s (1997, 30.) previously defined concept of “intersubjective analytic third”, which is formed by the interactions of the analyst and the analyzed, and can be imagined not so much as an entity but rather as an uninterrupted flowing process, which the participants experience differently and asymmetrically according to Ogden.

Other (post-) Jungian perspectives

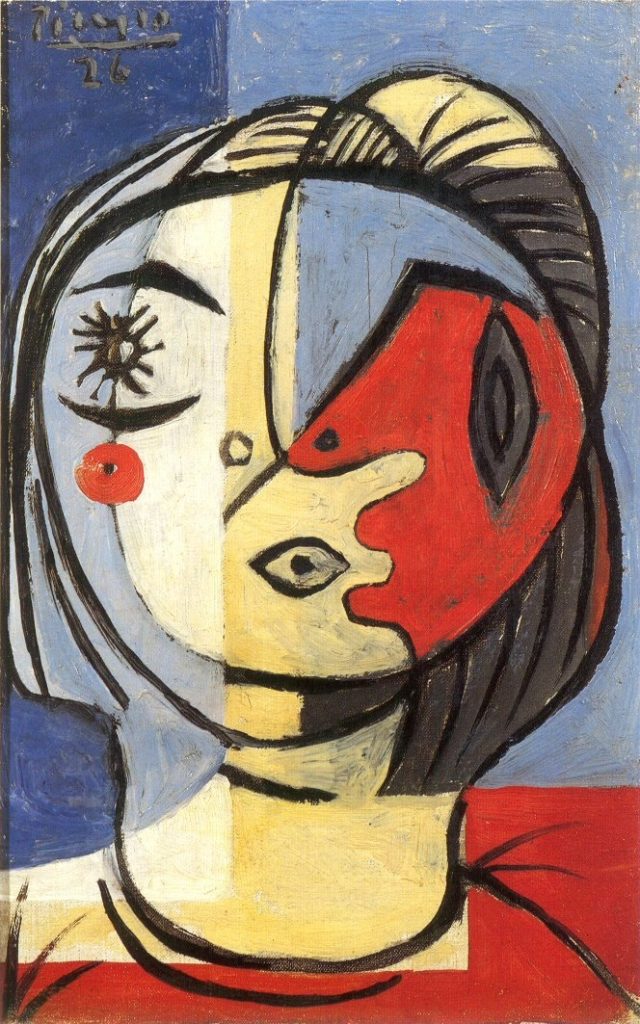

Many Jungian and post-Jungian authors have dealt with the phenomenon of various transference and countertransference processes and the particular “field” generated by the analytic dyad. For example, in his concept of “syntonic countertransference”, Michael Fordham (1957, as cited in Samuels, 1989, 107.) borrows the term “syntonic” from radiocommunication to explain how the analyst’s unconscious, as a “receiver” accurately tunes into what emanates from the patient as a “transmitter”, thereby discovering feelings and behaviours in himself or herself that relate to or express the patient’s inner world. Or we shall mention the concept of Guggenbühl-Craig (1971, as cited in Samuels, 1989, 108.), who follows the footsteps of Jung in identifying the analyst with the archetypal picture of the wounded healer, Cheiron, the centaur from Greek mythology, claiming on this basis that the healing process in the therapeutic situation is dependent on the alternation of reciprocal projection processes between the analyst and patient and the withdrawal of projections.

In his research on countertransference, Samuels (1985; 1989) interviewed thirty psychotherapists about their countertransference feelings during the analysis and found that the results could be grouped into two categories: the first one is reflective countertransference, in which the analyst takes over a particular internal, unconscious state of the patient, and as a result, his or her own feelings reflect the patient’s feelings; and the other one is embodied countertransference, the purpose of which is to create a physical, real, material, sensual expression of the patient’s internal content in the analyst, so part of the patient’s psyche can be embodied in the analyst. The latter phenomenon can be considered as nonverbal or preverbal, and according to the respondents, they are most common in cases where the patient has some kind of instinctual problem, for example problems related to aggression or sexuality, or eating disorders.

In his summary of embodied countertransference, relying on Samuels’ research, Stone (2006) examines the question from the perspective of the analyst and finds that if the analyst is unable to verbalise his or her intuitive feelings about the patient, his body can take them over. Furthermore propounding Jungian typology, he mentions a series of researches (e.g. Bradway, 1964; Plaut, 1972; Bradway & Detloff, 1976, 1996; Greene, 2001, as cited in Stone, 2006) and concludes that if the analyst has introverted intuition as primary function, he or she is presumably more prone to experience embodied countertransference.

Samuels (1985, 58–66.; 1989, 117–124.) adds another aspect to the study of countertransference, hoping that it may provide a deeper understanding of the nature of the phenomenon.

He uses a concept borrowed from Henry Corbin, a French philosopher, to try to capture the peculiarities of the imaginary space between the analyst and the patient – it is called mundus imaginalis, “imaginary world” and in Corbin’s view, it refers to a particular order or level of reality that lies between primary sense impressions and more developed cognition or spirituality. In the original French version the mundus imaginalis is referred to as “entre-deux” (Corbin, 1983, as cited in Samuels, 1989, 118.). Therefore, it denotes an in-between state or intermediate dimension that does not belong to either of the participants; in the therapeutic relationship, it simultaneously denotes the space between the analyst and the patient, the space between the conscious and unconscious levels of the analyst, and the analyst from the patient’s point of view, who is, on the one hand, a real person and, on the other, the location of transference projections. In his study, Stone (2006, 112.) draws parallels between Samuels’ concept and other authors’ ideas, for example Winnicott’s “transitional space”, „third area” and „area of illusion”, Schwartz-Salant’s „subtle body”, Searles’ „pre-ambivalent symbiosis”, Mihály Bálint’s “harmonious and interpenetrating mix-up” and Brown’s “unanxious confusion”. In addition, Stone cites a research carried out by Dieckmann and his colleagues (1974, as cited in Stone, 2006, 114.) who, in their long-term research on the analytic situation, found that even when countertransference remains uninterpreted, it can influence the whole analytic process.

The purpose of Dieckmann (1974, 1976) and his four colleagues was to write down any spontaneous association that arose along the psychic content shared by the patient in the analytic sessions, while it was also noted what was shared by the patient. The idea behind the method was that during the analytic process, the analyst usually tries to repress his or her own – sometimes disturbing – personal associations while concentrating on the unconscious processes of the patient, although these associations could also contain some useful information regarding the analytic situation. In their experiment, Dieckmann and his colleagues tried to avoid any repression and instead relate the arising emotions, fantasies and psychosomatic effects of the analyst with the patient’s material, all of which was later analysed together in a group analysis once every two weeks. In the first working period, they concentrated only on sessions that contained archetypal dreams, since they assumed that participation between the two people is greater under highly charged emotional conditions; later they started to select sessions by chance, numbering the sessions and then choosing one at random. The three-year-long experiment resulted in 37 patients in the first group and 12 patients in the second.

As the main results of the research (Dieckmann, 1976, 26.) show, they found that the analyst’s and the patient’s chain of association were in all cases psychologically significantly related to each other, even if they were not verbally shared with the patient during the session; moreover, in many cases, the analyst’s associations anticipated the associations of the patient. As another result, they found that the resistance appearing in transference and countertransference is often related to the fears and anxieties shared by both participants, meaning that resistance is not a one-sided problem based only on the patient’s attitude, but a matter that exists between the two people affecting each other. Their third observation was a significant increase in the phenomenon of synchronicity during the sessions, especially when the patient presented an archetypal dream – characterised by the presence of mythological motifs and strong, intense feelings – to the analyst, or during sessions with high emotional stress. Moreover, the phenomena of synchronicity and E.S.P. (extrasensory perception, a concept used in parapsychology) increased as the investigation proceeded, which might be explained by either an unconscious assimilation on the symbolic level, or a gained ability of the analyst to differentiate these kind of unconscious contents facilitated by the learning process of being attuned to subliminal perceptions.

Based on this, Dieckmann (op. cit. 31.) concluded that the basic foundation of the analytic situation is a synchronistic process. It means that an underlying archetypal dimension can be assumed to be present in the transference, presumably the Selbst in Jungian terms, which is responsible for the synchronisation of the chains of association between the analyst and the patient, and which directs the analytic process towards psychic growth, or also known as individuation. He also noted that feelings of countertransference were almost always associated with some kind of injury from the analyst’s personal history. Furthermore, Dieckmann (as cited in Burda, 2014, 28.) also raised the possibility that humans may have a still undiscovered ancient perceptual system that would explain biologically how these synchronous events can occur between two people.

Jung and synchronicity

The term “synchronicity” was proposed by Jung in a paper published in 1930; he described it as a connection between events in which there is no causal relationship but temporal simultaneity (Jung, 1930 [2003, 55–56.]). By synchronicity, Jung meant primarily a meaningful coincidence between the inner, psychic state and a simultaneously occurring external event.

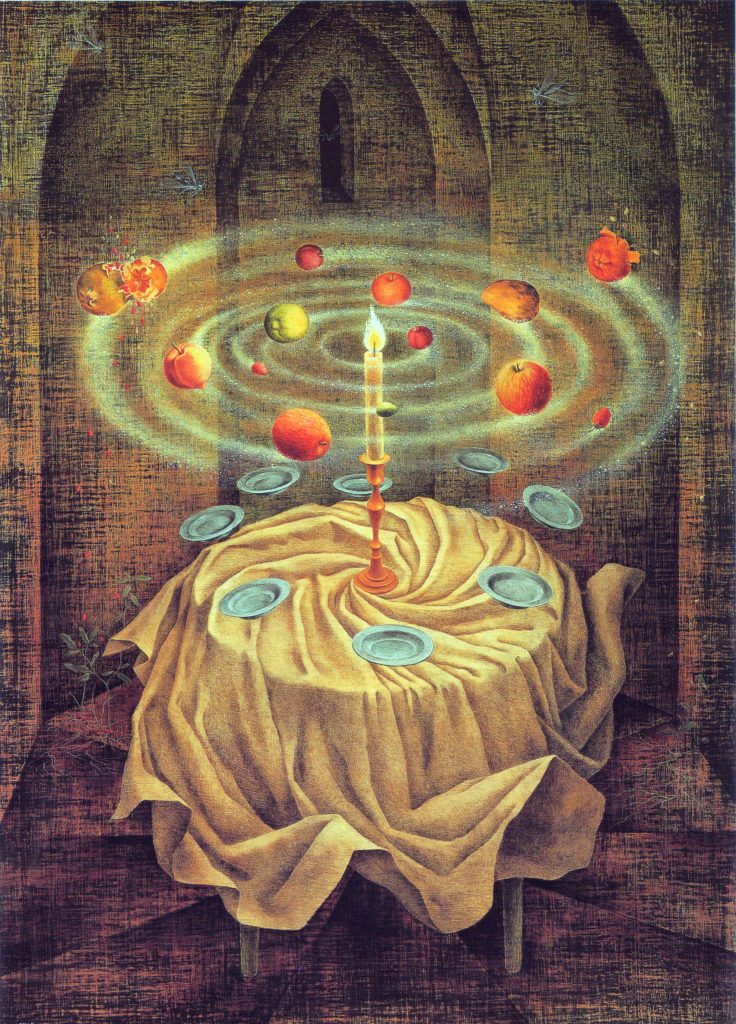

In his clinical work, he observed that synchronistic events tend to appear over and over again in the psychotherapeutic processes, especially during times of crisis and significant transformation; the unexpected encounter of internal and external realities seemed to induce an integrative healing process in the individual that lead toward psychological completeness (Jung, 1960 [2011, 109–110.]). In Jung’s view, the role of synchronicity was the same as the role of dreams, psychological symptoms or other manifestations of the unconscious: namely to compensate the conscious attitude and lead the psyche from problematic one-sidedness to a greater wholeness, thereby facilitating the individuation process. In his view, the underlying meaning that linked the synchronistic internal and external events was archetypal in nature.

To illustrate the phenomenon in his monograph, Jung (1960 [2011]) presents a case of a young woman, whose excellent education had provided her with strong intellectuality, although due to her undefeatable rationalism, she proved to be psychologically inaccessible, causing the treatment to stagnate. Then the following event happened:

“Well, I was sitting opposite her one day, with my back to the window, listening to her flow of rhetoric. She had had an impressive dream the night before, in which someone had given her a golden scarab – a costly piece of jewellery. While she was still telling me this dream, I heard something behind me gently tapping on the window. I turned round and saw that it was a fairly large flying insect that was knocking against the window-pane from outside in the obvious effort to get into the dark room. This seemed to me very strange. I opened the window immediately and caught the insect in the air as it flew in. It was a scarabaeid beetle, or common rose-chafer (Cetonia aurata), whose gold-green colour most nearly resembles that of a golden scarab. I handed the beetle to my patient with the words, » Here is your scarab«.” (op. cit. 109–110.)

As Jung reports, the synchronistic event effectively broke through the intellectual armouring that had been blocking her psychological development, so her treatment could be continued.

Synchronicity as emergence

In his study entitled Synchronicity as Emergence, Joseph Cambray (2004) examines the concept of synchronicity in the context of the history of psychoanalysis, parapsychology or early occultism and along the lines of the ideas of the “emergentists”. The emergentists were a group of simultaneous cultural and intellectual movements that developed mainly in English- and German-speaking countries in parallel with the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), one of the first key institutes for early parapsychological research, with as famous members as Frederic Myers, Charles Richet and William James (see also Ellenberger, 1970; Owen, 2004; Gyimesi, 2019). The main goal of the emergentists was to question the mechanistic worldview of scientific positivism of the 19th century by providing a more holistic approach to life and the universe; various holistic ideas, including Gestalt psychology originating from these perspectives. Famous members of the emergentists include John Stuart Mill, George Henry Lewes, Samuel Alexander, Conway Lloyd Morgan and C. D. Broad. Their theories could also have an impact on Jung’s thinking, for example in his paper entitled On the nature of the psyche, he uses an example borrowed from one of the lectures of Lloyd Morgan when constructing the theory of the archetypes (Cambray, 2004, 229–230.). Cambray also discusses the “complexity theory” developed by Nobel-prize winner chemist Ilya Prigogine, who is most noted for his work on thermodynamics of irreversible processes and non-equilibrium thermodynamics of dissipative structures, and who described how order can emerge through self-organisation at the edge of chaos in the case of self-organizing systems (e.g. living creatures). According to this, complexity as a feature of dynamic systems occurs when a new, hitherto unpredictable behaviour emerges from the interactions between components. This theory can be extended to many areas of life, e.g. certain chemical reactions, the weather, socio-political events, ecosystems, economic trends, even neural interactions of the brain.

A new research trend examining ‘complex adaptive systems’ (CAS) is based on complexity theory as well, which is unique in the sense that it tries to provide scientific evidence for the early intuitions of the emergentists. Researchers on CAS state that when it comes to adaptation, complex adaptive systems respond with emerging, self-organising properties under the influence of competitive constraints coming from the environment. Cambray argues that if we extend the emergent model to human psychology, these self-organising properties may seem “transcendent” from the point of view of human consciousness, also compared to how much we know about the behaviour of individuals. In this light, Jung’s concept of archetypal patterns may also seem much less speculative and more scientifically explainable, as Saunders and Skar (2001, as cited in Cambray, 2004, 232.) propose in their study, “the archetype is an emergent property of the activity of the brain/mind.”

Synchronicity in the therapeutic situation

In relation to the clinical, psychotherapeutic aspects of synchronicity, Cambray (2004, 233–234.) notes that, in some respects, the core of analytical work is openness to the emergent or potentially transformative properties of the psyche, the willingness to experience these aspects.

Based on the CAS model, he places the optimal mental state required for analytical work in the interface of order and chaos, in the “creative edge”, while noting that Jung himself called synchronicity the “act of creation”.

According to Cambray, the study of synchronistic events occurring in the clinical situation can be divided into two areas of discussion in the Jungian literature based on the applied focus: on the one hand, the emerging synchronistic events can be viewed as evidence of archetypal processes at work, demonstrating that the conscious personality is in connection with archetypal contents; and on the other, the emphasis is on the interactive aspects of the treatment, where the synchronistic events are interpreted along transference-countertransference dynamics. The latter approach is attributed to Michael Fordham (1957, as cited in Cambray, 2004, 235.), who argues that “synchronicity depends upon a relatively unconscious state of mind, i.e., an abaissement du niveau mental”, a term first formulated by Pierre Janet, meaning the lowering of the mental level. This fact could also explain why synchronicities tend to occur more often in stressful conditions, when important dimensions of awareness are lost by both parties (see Gordon, 1993, as cited in Cambray, 2004, 235.).

In their study on the psychotherapeutic aspects of synchronicity, Marlo and Kline (1998) note that the concepts of transference and countertransference are inextricably intertwined with synchronicity. The authors cite Jung’s thoughts (1961, as cited in Marlo & Kline, 1998, 18.), who noted, in connection with synchronicity, transference and countertransference that “the relationship between doctor and patient, especially when a transference on the part of the patient occurs, or a more or less unconscious identification of doctor and patient, can lead to parapsychological phenomena.” According to Marlo and Kline, one reason for this may be that transference, countertransference and synchronicity involve unconscious processes between internal and external objects and a shared, reciprocal relationship; thus, synchronistic events become meaningful and interpretable within the intersubjective system.

Regarding the clinical application of synchronicity, Marlo and Kline note that while synchronicity can be used in a variety of ways in psychotherapy, and in many cases, it plays a crucial role in a patient’s healing process, its abuse can be extremely harmful to the patient. One form of this is thoughtless or inappropriate disclosure or publication of a synchronistic experience. According to the authors, the therapist should evaluate the unconscious communication in the analytic relationship with great care, utilising his or her knowledge of the patient’s development, fantasies, transference, personality and needs in addition to his or her knowledge of the symbolic meaning of the synchronistic event, and constantly monitoring the impact of his or her words on the patient when gauging the usefulness of disclosure. Keutzer (1984) provides similar arguments on this and adds that the main way to use synchronicity is when the therapist focuses on the patient’s side of the synchronistic event, which can prevent undesirable consequences.

Another important aspect to take into account is the ego structure of the patient (Marlo & Kline, 1998, 19–20.). Patients who have more primitive ego structures, although they fundamentally have easier access to unconscious material, which makes them more capable of analysing synchronistic events, can take interpretations too literally and become frightened, disorganised, or act out. The authors say it is not inevitable, although exercising due caution is recommended for the therapist. In addition, they note that the utilisation of synchronicity does not always require verbal discussion of the synchronistic event or connection, which means that the therapist may choose to use it without even letting the patient know. Finally, the authors add that the therapists should also evaluate their own development, needs, and feelings of countertransference in cases where the disclosure of synchronicity arises, since if they are guided by their own unresolved problems, interpretation can cause significant and irreparable damage.

Conclusion

Parapsychological phenomena have been present in psychoanalytic discussion since the early period of psychoanalysis; for example the issue of telepathy has been studied by several significant authors, such as Freud, Ferenczi, Bálint, and Helen Deutsch (see Devereux, 1953; Gyimesi, 2019). Although theories have been developed to explain some phenomena, and the majority of the authors agreed that certain, seemingly supernatural phenomena can be explained as manifestations of the unconscious, the majority of definitions remain incomplete.

Synchronicity, like telepathy, is an undeveloped concept. Perhaps partly for this reason, it is gaining wide-scale popularity in professional circles today – especially in Jungian ones – and an increasing amount of studies are being made on the subject: e. g. concerning its history (Donati, 2004; Zabriskie, 2005; de Moura, 2014; Main, 2014; Stein, 2015), its relation to clinical practice (Reiner, 2006; Todaro-Franceschi, 2006; Hogenson, 2009; Carvalho, 2014; Roxburgh, Ridgway & Roe, 2015; Smith Klitsner, 2015), to astrology (Tarnas, 2006; Le Grice, 2009; Smith Klitsner, 2015; Buck, 2018) and other occult or esoteric practices (Main, 2014; Payne-Towler, 2020), by connecting Jungian psychology and quantum physics through synchronicity (Mackey, 2005; Zabriskie, 2005; Tougas, 2014; Stein, 2015; Baum, 2018), not to mention the critiques of the studies made on the subject, or of the theory itself (Yiassemides, 2011; Giegerich, 2012; Kime, 2019).

Based on the diversity of standpoints and the ability to link the topic to different disciplines, we can say that the issue of synchronicity is almost inexhaustible. If we only investigate the phenomenon of synchronicity in its relation to transference and within the psychoanalytic context, it points to fairly important factors that we should not ignore when considering the workings of the psyche. Although we still have little understanding of the mechanisms at work behind this peculiar experience – especially at a biological level –, hopefully as a result of the growing interest, consensus will soon be reached.

References

Baum, R. (2018). A Walk on the Beach with Jung. Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche, 12(4): 73–87.

Bradway, K. (1964). Jung’s psychological types: Classification by test versus classification by self. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 9(2): 129–135.

Bradway, K. – Detloff, W. K. (1976). Incidence of Psychological Types: Among Jungian analysts classified by self and by test. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 21(2): 134–146.

Bradway, K. – Detloff, W. K. (1996). Psychological type: A 32-year follow-up. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 41(4): 553–574.

Buck, S. (2018). Hiding in plain sight: Jung, astrology, and the psychology of the unconscious. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 63(2): 207–227.

Burda, J. (2014). Wounded Healers in Practice: A Phenomenological Study of Jungian Analysts’ Countertransference Experiences. Dissertation. Antioch University, US, Ohio. http://aura.antioch.edu/etds/152, downloaded: 2020. 05. 15.

Cambray, J. (2004). Synchronicity as emergence. In: J. Cambray & L. Carter (Eds.), Analytical Psychology. Contemporary Perspectives in Jungian Analyisis (223–248). East Sussex: Brunner-Routledge.

Carter, L. (2010). Countertransference and Intersubjectivity. In: M. Stein (Ed.), Jungian Psychoanalysis. Working in the Spirit of C. G. Jung (201–212). Chicago: Open Court.

Carvalho, R. (2014). Synchronicity, the infinite unrepressed, dissociation and the interpersonal. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 59(3): 366–384.

Corbin, H. (1983). Theophanies and mirrors: idols or icons? Spring: An Annual of Archetypal Psychology and Jungian Thought, 198: 1–2.

de Moura, V. (2014). Learning from the patient: The East, synchronicity and transference in the history of an unknown case of C.G. Jung. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 59(3): 391–409.

Devereux, G. (1953). Psychoanalysis and the Occult. London: International University Press.

Dieckmann, H. (1974). The constellation of the countertransference in relation to the presentation of archetypal dreams: Research methods and results. In: G. Adler (Ed.), Success and Failure in Analysis (69–84). New York: Putnam.

Dieckmann, H. (1976). Transference and countertransference: Results of a Berlin research group. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 12: 25–35.

Donati, M. (2004). Beyond synchronicity: the worldview of Carl Gustav Jung and Wolfgang Pauli. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 49(5): 707–728.

Ellenberger, H. F. (1970). The Discovery of the Unconscious. The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. London: Fontana Press.

Fordham, M. (1957). New Developments in Analytical Psychology. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Freud, S. (1910). The future prospects of psycho-analytic therapy. In: Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis. Leonardo da Vinci and Other Works. CPW XI. (139–152). London: Hogarth, 1957.

Freud, S. (1913). The Disposition to Obsessional Neurosis, a Contribution to the Problem of the Choice of Neurosis. In: The Case of Schreber. Paper on Technique and Other Works. CPW XII. (311–326). London: Hogarth, 2001.

Gallese, V. (2001). The ‘Shared Manifold’ Hypothesis. From Mirror Neurons to Empathy. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8(5–7): 33–50.

Giegerich, W. (2012). A serious misunderstanding: synchronicity and the generation of meaning. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 57(4): 500–511.

Gordon, R. (1993). Bridges: Psychic Structures, Functions, and Processes. London: Karnac.

Greene, A. U. (2001). Conscious mind: Conscious body. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 46(4), 565–590.

Guggenbühl-Craig, A. (1971). Power in the Helping Professions. New York: Spring Publications.

Gyimesi, J. (2019). A szellemektől a tudattalanig. [From Spirits to the Unconscious.] Budapest: L’Harmattan.

Hill, J. (2010). Amplification: Unveiling Emergent Patterns of Meaning. In: M. Stein (Ed.), Jungian Psychoanalysis. Working in the Spirit of C. G. Jung (109–117). Chicago: Open Court.

Hogenson, G. B. (2009). Synchronicity and moments of meeting. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 54(2): 183–197.

Iacoboni, M. (2009). Imitation, Empathy, and Mirror Neurons. Annual Review of Psychology, 60: 653–670.

Jacobi, J. (1999). Complex/Archetype/Symbol in the Psychology of C. G. Jung. London: Routledge.

Jung, C. G. (1931). Problems of Modern Psychotherapy. In: Jung: Practice of Psychoterapy. CW 16 (84–115). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985.

Jung. C. G. (1946). Psychology of the Transference. In: Jung: Practice of Psychoterapy. CW 16 (227–417). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985.

Jung, C. G. (1985). Practice of Psychotherapy. CW 16. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1930). Richard Wilhelm emlékére. [In memory of Richard Wilhelm.] In: Jung: A szellem jelensége a művészetben és a tudományban (53–61). Budapest: Scolar, 2003.

Jung, C. G. (1960). Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Keutzer, C. S. (1984). Synchronicity in Psychotherapy. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 29: 373–381.

Kime, P. (2019). Synchronicity and meaning. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 64(5): 780–797.

Le Grice, K. (2009). The Birth of a New Discipline. Archetypal Cosmology in Historical Perspective. Archai: The Journal of Archetypal Cosmology, 1(1): 2–22.

Mackey, J. L. (2005). The New Sciences. The San Francisco Jung Institute Library Journal, 24(2): 75–84.

Main, R. (2014). The cultural significance of synchronicity for Jung and Pauli. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 59(2): 174–180.

Marlo, H. – Kline, J. S. (1998). Synchronicity and Psychotherapy: Unconscious communication in the psychotherapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy, 35(1): 13–22.

Ogden, T. H. (1997). Reverie and Interpretation. Sensing Something Human. New Jersey: Jason Aronson Inc.

Owen, A. (2004). The Place of Enchantment. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Payne-Towler, C. (2020). Synchronicity and Psyche. Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche, 14(2): 64–90.

Plaut, A. (1972). Analytical Psychologists and Psychological Types: Comment on replies to a survey. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 17(2): 137–151.

Reiner, A. (2006). Synchronicity and the capacity to think: a clinical exploration. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 51(4): 553–573.

Roxburgh, E. C. – Ridgway, S. – Roe, C. A. (2015). Synchronicity in the therapeutic setting: A survey of practitioners. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 16(1): 44–53.

Samuels, A. (1985). Countertransference, the “mundus imaginalis” and a research project. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 30: 47–71.

Samuels, A. (1989). The Plural Psyche. Personality, Morality and the Father. London: Routledge.

Saunders, P. – Skar, P. (2001). Archetypes, complexes and self-organization. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 46(2): 305–323.

Smith Klitsner, Y. (2015). Synchronicity, Intentionality, and Archetypal Meaning in Therapy. Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche, 9(4): 26–37.

Stein, M. (2015). From Symbol to Science. Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche, 9(1): 7–17.

Stone, M. (2006). The Analyst’s Body as Tuning Fork: Embodied Resonance in Countertransference. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 51: 109–124.

Tarnas, R. (2006). Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. US, NY, New York: Penguin Group. eBook version.

Todaro-Franceschi, V. (2006). Synchronicity related to dead loved ones as a natural healing modality. Spirituality and Health International, 7(3): 151–161.

Tougas, C. T. (2014). Causality as individual essence: Its bearing on synchronicity. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 59(3): 410–420.

Yiassemides, A. (2011). Chronos in synchronicity: Manifestations of the psychoid reality. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 56(4): 451–470.

Zabriskie, B. (2005). Synchronicity and the I Ching: Jung, Pauli, and the Chinese Woman. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 50(2): 223–235.

Kanász Nikolett klinikai szakpszichológus jelölt, a Pécsi Tudományegyetem Elméleti pszichoanalízis doktori programjának hallgatója.

A tanulmányt a szerző hozzájárulásával közüljük, nyomtatásban az Imágó folyóiratban olvasható (2021, 10/01, Budapest, 30-41.).